Juul’s popularity tests anti-smoking efforts

Despite risks, many believe vapes are a safe alternative to smoking

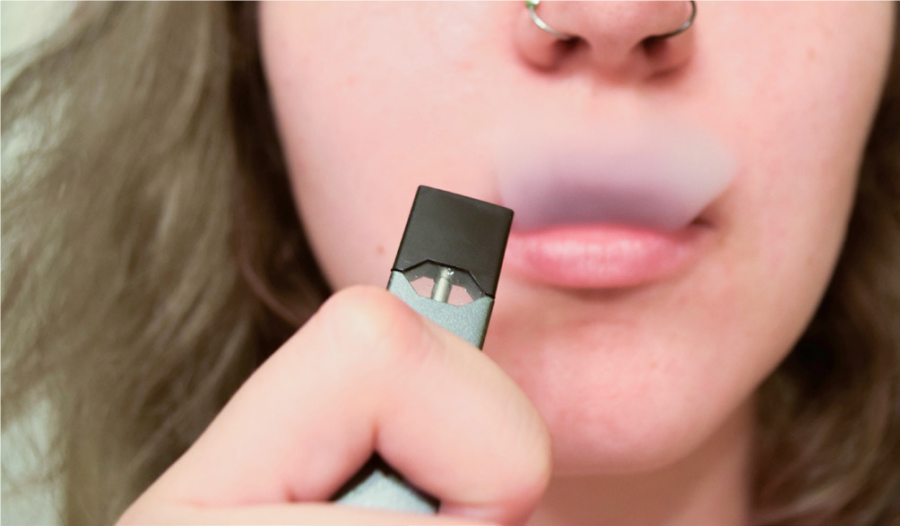

E-cigarettes, like Juul, are included in the BW tobacco ban despite misconceptions of some students.

The rapid rise in popularity of the Juul vaporizer has led to national conversations about the health implications of vaping among youth and young adults.

A product barely younger than BW’s January 2017 campus-wide smoking and tobacco ban, Juul’s unprecedented popularity among young people prompted the FDA to release a statement in September condemning youth vaping as an “epidemic.”

Juuls, like other vape or e-cigarette products, are a type of electronic nicotine delivery system. Such devices operate by heating a liquid cocktail of nicotine, flavoring and additional additives to produce an aerosol that is inhaled by the user. Juul contains more nicotine than most e-cigarettes: the company claims that one “pod” of e-liquid is equivalent to a pack of 20 cigarettes.

Despite its popularity as a cigarette alternative, as nicotine is a derivative of the tobacco plant, vape devices like Juul are included in BW’s ban. The policy, which began as a student government initiative, prohibits the use of “cigarettes, pipes, cigars, e-cigarettes, smokeless and chewing tobacco” on campus property.

While BW prohibits vaping on campus, , like a number of other Ohio colleges and universities including Cuyahoga Community College and Kent State, the question of where vaping is appropriate or allowed is being debated across the state and the country.

In Ohio, the 2007 Smoke-Free Workplace Act prohibits smoking in public places and places of employment but does not address the use of electronic nicotine delivery systems. While certain localities have banned vaping where smoking is not allowed, the issue is largely unaddressed by state policy.

Professor Wendy Hyde, assistant professor of health, physical education and sports science at BW, is an active advocate for the non-profit Preventing Tobacco Addiction Foundation and was a member of the team that developed BW’s smoke and tobacco-free policy. Hyde said that rather than merely eliminating smoke on campus, the ban is intended as a campus health initiative and that includes avoidance of electronic nicotine delivery systems.

“Tobacco smoke itself is dangerous: we know there are carcinogens and such in the tobacco smoke,” she said. “However, this is about reducing nicotine addiction.”

Youth and young adult use

Nicotine is known to have negative effects on the adolescent brain, which continues to develop until about age 25. According to the CDC, there is “no safe level” of nicotine consumption for youth and young adults, whose developing brains are more susceptible to nicotine addiction than adults aged 26 and older. Because of youth susceptibility to nicotine addiction, and Juul’s profile as a seemingly “safe” alternative to smoking, anti-tobacco non-profits are focusing on addressing preventing youth vaping.

Despite the risk of nicotine to developing brains, vape and e-cigarettes are not subject to all of the restrictions and regulations that apply to traditional cigarettes.

Hyde said that she thinks that vape products are the “trojan horse put out by the tobacco industry” because though they were initially put on the market as a device to aid smokers who wanted to quit the habit, she thinks that vapes are intentionally made to appeal to youth and get them hooked on nicotine.

Alex Morrow, a senior music education major at BW, disagrees. Morrow, a former heavy cigarette smoker, said that the day he bought his Juul this summer is the day he stopped smoking.

Morrow said that he believes that the Juul company is “really dedicated to helping smokers” quit cigarettes. He said that unlike other vaping devices, “the way it hits” is a similar sensation to smoking a cigarette.

When he was smoking his heaviest, a pack of 20 cigarettes would last Morrow two days; now, he says one Juul pod will last him about a day and a half.

Morrow said that it is easier to consume high amounts of nicotine with a Juul than with traditional cigarettes and therefore Juul is more addictive. He agrees that it is unsafe for kids with developing brains to start using Juul, though he does not think that the product is to blame for its misuse.

“I don’t think it’s an issue with the product itself. I think the product is what it is and for the people it’s marketed for, it’s good,” said Morrow. “But the thing is it’s marketed for young adults who have begun smoking, young millennials who have begun smoking and want to stop to better themselves. And because of that, we see the younger generation … look up to the generation above it and say ‘I want to be like them.’”

In response to FDA concerns about vapes and Juul in particular appealing to youth, Juul released a statement saying that their “mission is to eliminate cigarette smoking” and that they “fully support the FDA’s efforts to curb underage use of tobacco products.”

Vapes as cessation tools

Hyde, for her part, is skeptical that they vape industry actually wants people to quit smoking or using tobacco products.

She’s not alone. The non-profit Truth Initiative notes that there are “substantial research gaps in proving the effectiveness” of e-cigarettes as cessation aids. While there is some evidence that supports the use of e-cigarettes as cessation aids, e-cigarettes are most commonly used by those who also currently use other tobacco products, such as traditional cigarettes.

Additionally, there is “substantial evidence” that e-cigarette use increases the likelihood of trying cigarettes or other combustible tobacco products, according to the Truth Initiative.

“The industry tries to say that this is a quitting mechanism, but very few actually quit, or very few actually quit using nicotine products altogether,” said Hyde. “And more often than not, we have the young adult users are the ones that are starting to use the products, including Juul.”

For his part, Morrow noted that of the “seven or eight” people he knows who use a Juul, only one is not using it to aid in quitting cigarettes.

Apart from the increased risk of using other tobacco products, vapes themselves may pose additional health risks. According to the Truth Initiative, e-cigarette use is “substantially less harmful” and contains fewer toxins than combustible cigarette smoke, but the aerosols still deliver harmful chemicals and are largely untested from a long-term health perspective.

In other words, using e-cigarettes does not guarantee you’re free of health risk, said Hyde.

“If you’re looking at e-cigarettes, they’re still a fairly new product, so the research really is not complete yet as to long-term health effects of the product,” said Hyde.

Morrow said he is aware of the risks that Juul could potentially pose, but isn’t too concerned about them.

“If a study comes out that says you should not use Juuls because there will be no immediate effects, but 20 years down the line your lungs are going to implode, I would stop using it,” said Morrow. “But I don’t think that that medical report is going to come out anytime soon, both because of the lack of study and because I don’t think that’s the case, personally.”

Tobacco use on campus post-ban

Though BW offers cessation resources for smokers looking to quit, Sam Ramirez, assistant vice president for human resources who “spearheaded” the smoking ban policy writing, said that there have not been many on campus who have taken advantage of them.

Morrow, for his part, was among those who passed on the university’s cessation resources because he wasn’t looking to quit. Rather, as a self-described “heavily nicotine addicted person,” he was looking for a “better product” that had the same effect on him.

Morrow said that he and other students find BW’s campus smoking and tobacco ban to be “not very clear” in that it doesn’t seem to him to be explicit whether vapes like Juul are banned. Considering a recent study that reported that only 37 percent of Juul users know that the product always contains nicotine, Hyde said it’s possible that there could be misconceptions on campus about Juul’s place in the tobacco ban.

“We had done a pretty good campaign [for the new policy] several years ago when we first went smoke-free, tobacco-free here on campus; however, that was two years ago, said Hyde. “I’m not sure how many students, especially if they’re new to the campus, are familiar with the policy.”

Though some students may be unaware of the policy, Morrow said he feels like the policy isn’t enforced: he knows several students who regularly vape on campus, sometimes in the presence of university employees, and have not been penalized.

His experience is not necessarily unfounded. Ramirez said that the enforcement of the policy is “loose” and that penalties for violation would be determined on a case-by-case basis.

Overall, Morrow said doesn’t feel like the ban has done much to reduce campus nicotine consumption.

“I understand [the smoking ban] as a campus health initiative, but I don’t think it’s the best way to go about it, in my opinion, and I don’t think it was productive,” said Morrow. “I think that Juul coming out was more effective at banning smoking on campus than the campus smoking ban was.”

The university does not currently have data about BW community members who use vapes or other tobacco products, but Hyde said she would be interested to know how prevalent vaping is across campus as a matter of campus wellness.

“We want a healthy student population,” she said.

The Exponent is looking for financial contributions to support our staff and our newsroom in producing high-quality, well-reported and accurate journalism. Thank you for taking the time to consider supporting our student journalists.