Just one day before the assassination of conservative activist Charlie Kirk on the campus of Utah Valley University, a national poll was released that suggests college students are increasingly supportive of using acts of violence to stop a campus speech.

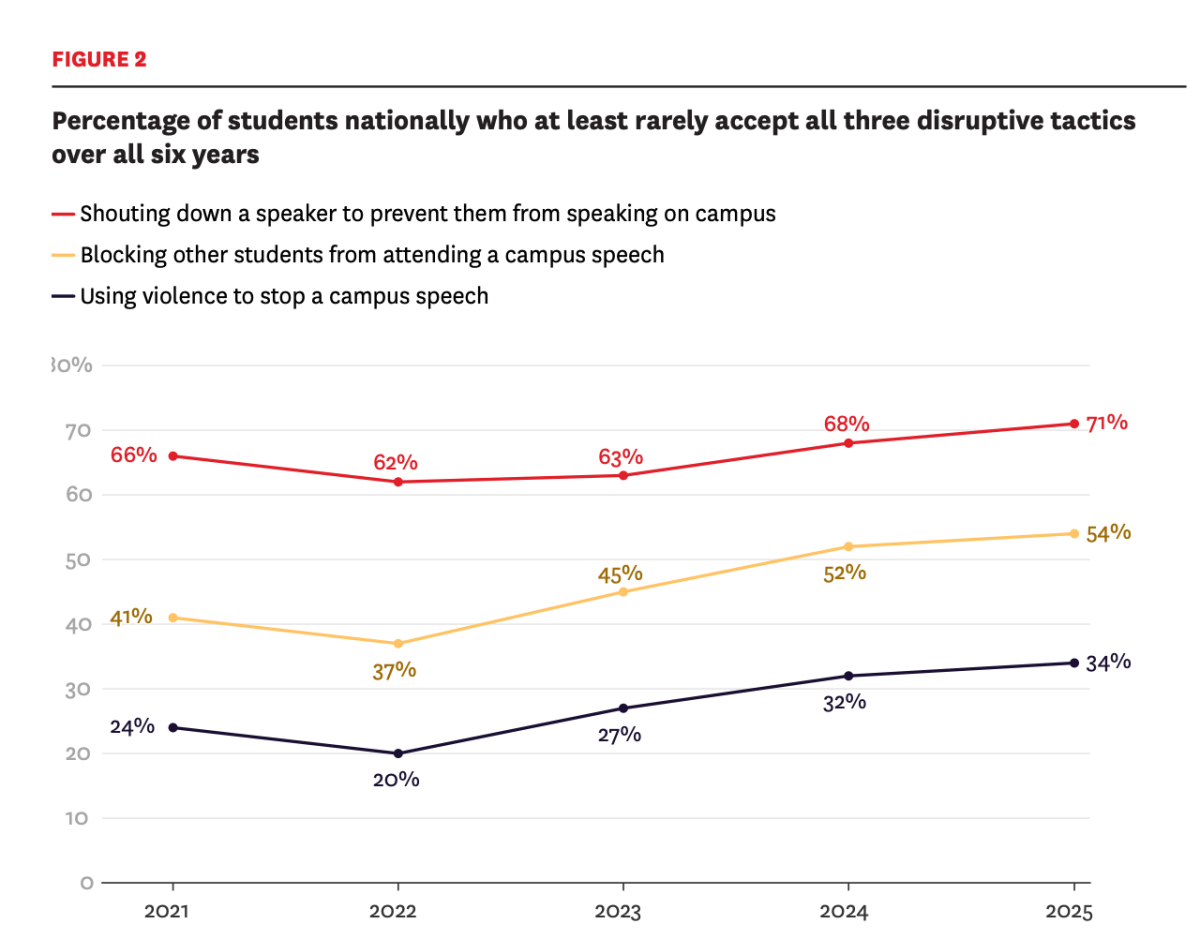

The poll, conducted by Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, an organization that defends and promotes individual rights, particularly free speech, found that 34% of college students in America answered that they would “at least rarely accept” using violence to stop a campus speech. This number is up from 20% in 2022, a nearly 80% increase.

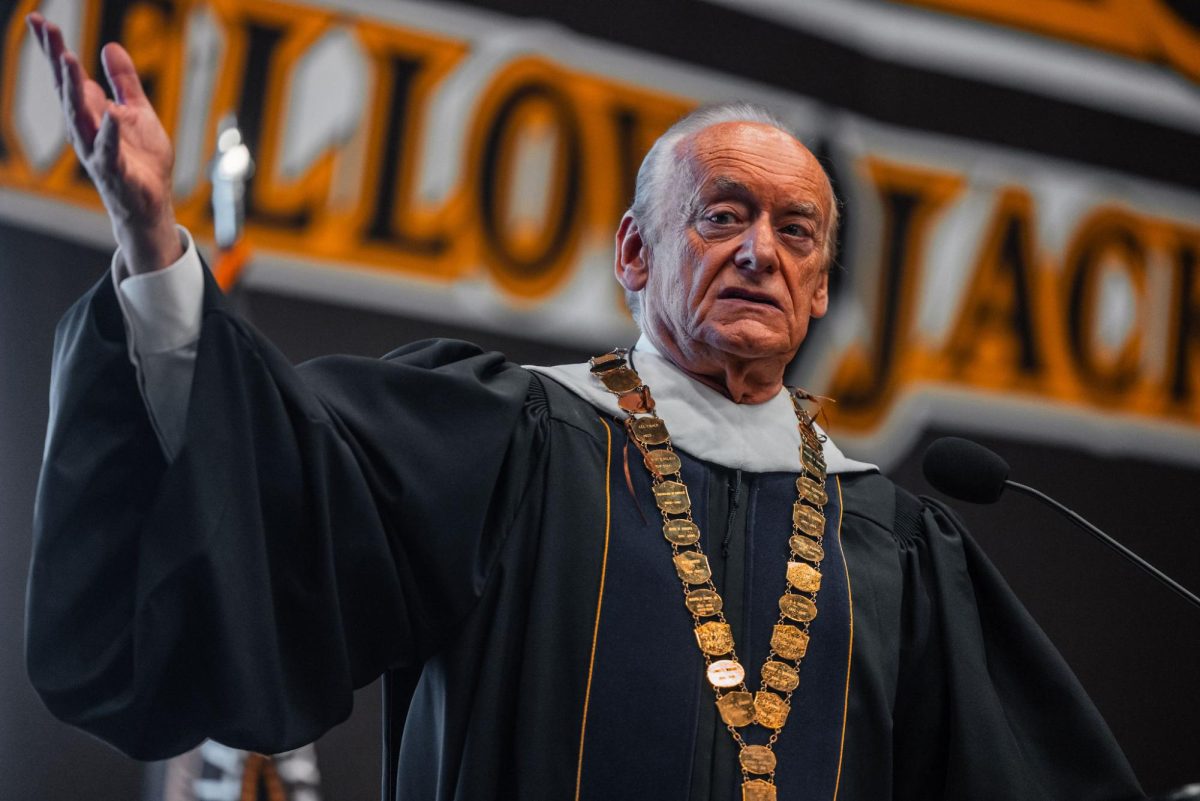

In an email to students, Baldwin Wallace University president Lee Fisher shared the FIRE poll, and told students in bold print, “That’s not us.” He affirmed that BW has always been, and will continue to be, a place where ideas are debated with curiosity instead of hostility, and with respect instead of violence.

“Campuses like ours must be front line protectors of the U.S. Constitution and our First Amendment,” Fisher wrote. “By promoting civil discourse, we help protect free speech – including the freedom to share ideas, no matter how varied and diverse.”

Considering these recent findings, and with Kirk’s killing being immediate evidence of that, one question looms large: How can America combat the idea that violence is an acceptable response to political and moral disagreements?

Kelly Coble, a professor of philosophy and religion at BW, and Theron Quist, chair of the sociology department at BW, both mentioned divisive political discourse and social media platforms as reasons that could be contributing to this increasing polarization.

“We have discourse on both sides of the political spectrum that regards the other side as irredeemably wicked,” Coble said. “Just absolutely, existentially, unacceptably bad… I think we shouldn’t participate in that kind of discourse.”

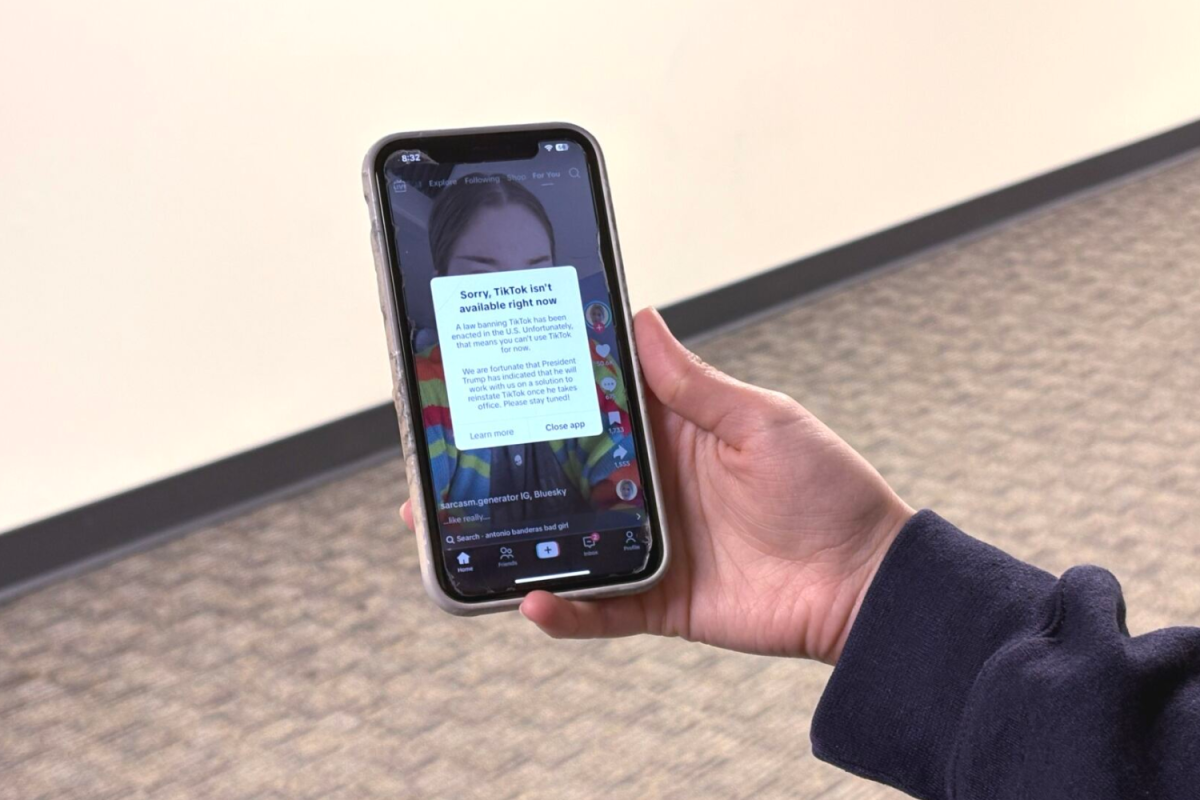

Coble also said that he blames “big tech” for fostering a toxic social media environment that uses algorithms to boost “divisive” and “enraging” posts.

“[These corporations] need to generate revenue, I get that,” Coble said. “On the other hand, at what cost? I think that these algorithms are contributing significantly to the toxic quality of our social media conversations.”

Quist said social media encourages a cycle of anger and hurt where people react online without considering how it may come off to those around them. Quist emphasized the importance of being “peacemakers” amidst strong disagreement, instead of seeing someone else only as a political opinion that you disagree with.

“When so much of our interaction occurs electronically there is a tendency to only see a person for their most recently stated opinion, which you may not agree with,” Quist said.

CJ Harkness, director of spiritual life at BW, explained the spiritual aspect to the survey results, saying that America has lost touch with elements of spirituality, such as a connection to the divine as well as a connection to one another. When we lose this connection, it leads to a greater willingness to harm others.

“I don’t think we see a divine nature in whoever it is that we might define as the ‘other,’” Harkness said. “If you [believe that life is sacred], then something has to happen when you see a life that you no longer have restraint from harming.”

Quist offered another possible reason for the results of the survey: that recent generations of college students have been overprotected and have not been allowed to feel sufficiently uncomfortable.

Quist cited research from Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff, authors of the book “The Coddling of the American Mind,” who studied college students about a decade ago. According to them, things like less unstructured play time and more screen time meant that generation had less opportunities to work out interpersonal conflicts in healthy ways.

Quist said that, around this time this research was being done, campus “safe spaces,” places where a category of people can feel confident they won’t be exposed to emotional or physical harm, and trigger warnings, statements given before a piece of writing, video, etc., alerting the viewer of potential distressing material, became more prevalent to prevent discomfort.

While Quist recognizes there may be a time and place for such things, he also said, “perhaps we went too far with them.”

Quist then addressed an idea that stems from Haidt and Lukianoff’s research, what he calls the “most extreme version of this phenomenon”: “that hurtful words are forms of violence,” and therefore, “answering words with violence is acceptable in some situations.”

“So long as we have a significant minority of people who believe that unpleasant or hurtful words should be met with violence, we will struggle through more literal violence in this country,” Quist said. “Freedom of speech should mean that we protect the right of others to say things that we don’t like.”

Taking these many possible causes into account, Coble and Quist both offered hope and advice for working toward a greater commitment to free speech, unity and mutual respect in America.

Coble said that, as a step towards combatting the “mainstreaming of discourse that tolerates and promotes political violence as a means of achieving political goals,” America’s leaders must firmly condemn such ideas, on both sides of the political aisle.

“Our political leaders have a grave and sacred duty to speak with moral clarity on these issues,” Coble said. “Calling for unity at times of crisis like this is a minimum standard to hold our leadership to.”

Coble specifically cited encouraging examples he has seen recently, such as many Democratic politicians’ widespread condemnation of Kirk’s killing, and Donald Trump and former Republican House Speaker Paul Ryan’s compassion and moral clarity in their speeches following the shooting at a practice session for the 2017 Congressional Baseball Game.

Coble also emphasized that other groups besides political leaders bear some responsibility in upholding America’s core values. Among these groups are educators, parents, families, communities, friends, cultural leaders and athletes.

For Coble, American values are deeply rooted in the idea of a democratic republic that America was founded on. He said that he worries America is losing sight of such core values as non-violence and rule of law, and that a more widespread and deeper awareness of these democratic values is needed in America.

Coble said that, to start, primary and secondary education could more intensely focus on civics, how America’s government works and what it is supposed to achieve, and “why democracy is a good thing.”

“One of the reasons why democracy is a great thing is because it provides an alternative to political violence for pursuing political change,” Coble said.

Harkness said that something that can cloud moral clarity is fear, including fear of an “other” group. He said that when “fear is driving our practice,” it undermines love, which, for Harkness, entails justice, not retribution.

“Moral clarity calls for justice, fear calls for retribution,” Harkness said.

On a more local level, one question that lingers is this: If BW had hosted somebody like Charlie Kirk, what would its reaction have been?

Quist said that it is his experience that most people at BW are generally willing to hear opposing viewpoints even if they disagree. Still, he also offered practical advice for growing even more in the commitment to respectful dialogue and the free exchange of ideas.

“The next time you’re having a meal and somebody shares something with which you disagree, pause and ask them to tell you more about their experiences and feelings,” Quist said.

“Students need to develop the difficult skill of tolerating the expression of views they find repugnant; they also need to develop the skill of challenging those views and doing so in a civil way, which can be difficult when emotions run high,” Coble said. “We must also practice the difficult skill of empathy, trying to imagine how our words might affect absolutely everyone in the room.”

Harkness said it is an evil lie that violence will bring any fulfillment, and that Americans cannot change hearts and minds without engaging with one another in real life.

“You have to become human to me again,” Harkness said.

Quist said that these tragic events we hear about in the media are generally less common than most Americans perceive them to be, but still recognized the risk that comes with speaking one’s mind. For Quist, the risk is worth it.

“In any situation there are risks, so we must weigh out the risk of danger compared to the risk of not speaking out on what we feel to be right,” Quist said. “If we are silenced, then those willing to be violent will win. Open dialogue is our best hope of rising above our current polarized state, and standing up for that is worth the risk.”

Shawn Salamone • Sep 24, 2025 at 12:24 pm

Some great comments here about civil discourse and I’m proud that fostering skills to dialogue across differences remains a priority at BW.

I will caution that before take the stat cited at face value, dig deeper into why polling on this issue is notoriously off in the recent New York Times piece titled, “Why Support for Political Violence Is Not as High as It May Seem”

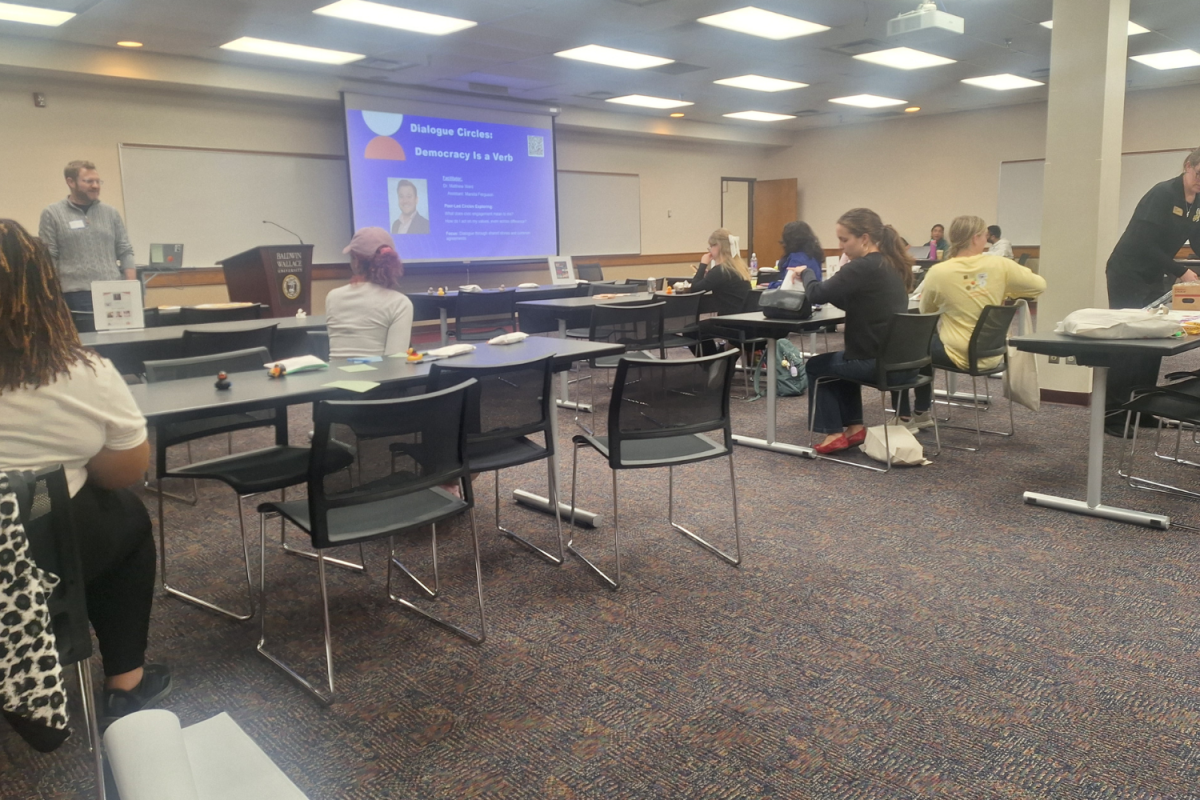

Finally, I want to pass along the invitation to attend the 2025 Northeast Ohio Democracy & Dialogue Summit at Baldwin Wallace University on October 11, 2025. The Democracy & Dialogue Summit invites students, staff, and community members to come together for a powerful day of reflection, action, and connection around one central question: What does it mean to show up for democracy? Watch for details.