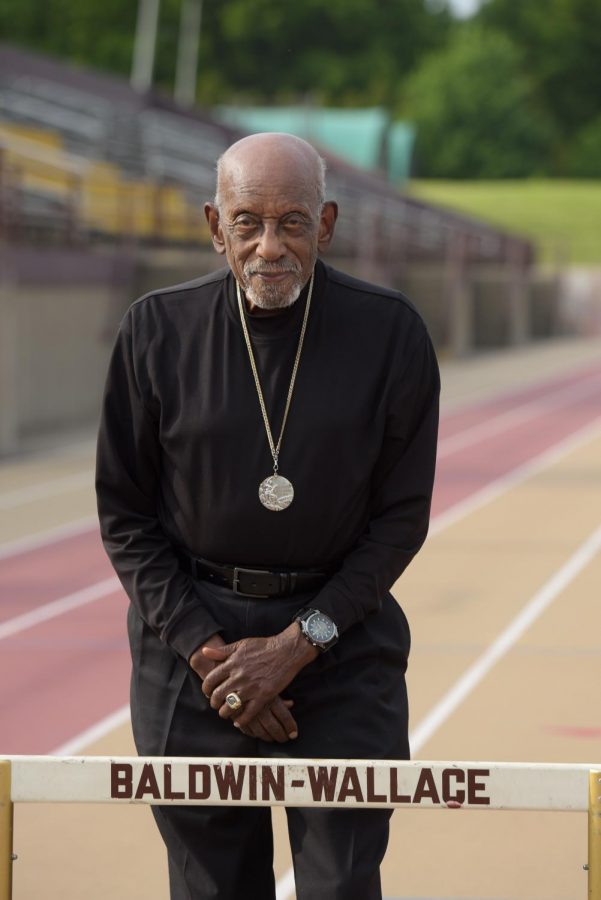

‘One of the giants of Baldwin Wallace’

Harrison Dillard, 1949 grad and four-time Olympic gold medal winner, passes away

Harrison Dillard never outgrew Northeast Ohio.

In between graduating from East Technical High School in Cleveland and graduating from Baldwin Wallace in 1949, Dillard won two Olympic gold medals. Then, three years after graduating college, he won two more gold medals at the Helsinki Olympics.

Some six decades later, Dillard is still the only man to win an Olympic gold medal in a hurdling event and a sprinting event, and the only Baldwin Wallace student to have ever won an Olympic medal.

On Nov. 15, Dillard passed away. He was 96.

With four Olympic gold medals, 14 AAU hurdle championship wins, and the 1953 Sullivan Award all to his name, Dillard goes down in Baldwin Wallace history as one of the school’s most decorated alumni.

“He’s one of those heroes of BW,” President Bob Helmer said. “He accomplished something really incredible but didn’t stop there. He set about making his life work all about inspiring other people.”

Long after his time on the track or on campus, Dillard played an active role with BW students, said Kevin Ruple, the Director of Athletic Communications and Public Relations, who spent over 30 years as the Sports Information Director. He said that Dillard never focused on himself, but rather the team or group around him.

“He had this humanistic impact. We were going to one of the big relays, like the Penn Relays or Drake Relays. Someone sent Harrison a plane ticket to fly to it,” Ruple said. “But Harrison cashed that plane ticket in and had enough money to take the entire BW team to the relays. So, they got on a train and I think that shows he wasn’t just a great individual athlete but a team athlete and a leader.”

Dillard traveled the world, from serving in Italy during World War II to winning Olympic gold medals in London and Helsinki, but somehow, he always found his way back to the campus of Baldwin Wallace.

But out of all the visits back to campus, there was one particular example that stuck out to Helmer, and even he wasn’t sure if it was going to happen.

When the BW Women’s Indoor Track and Field team won the National Championship in 2016, the first visit from an alum came from Harrison Dillard, who surprised them at a dinner after they returned to campus.

On the night of the surprise visit, the weather was less than pleasant, recalled Helmer. He had invited the championship winning team to his house for dinner but when the team had arrived and dinner had been served, there was one open seat left at the table.

Only one person knew who it was for.

“Dinner was supposed to be at 5, and I had it all set up, but there was that open chair,” said Helmer. “And the women are all asking who else is coming, and it’s 5:15, 5:30 rolls around and I said something like ‘I don’t know if they’re coming.’ And then at ten ‘til six, there was a knock at the door, and you would have thought Santa Claus just came through the door. All of the student athletes are like, ‘oh my God, Harrison Dillard is here,’ and then I couldn’t get any of them to leave that night.”

As a child, Dillard would pretend he was an Olympian.

He would take the springs from abandoned car seats and set them up as barriers in alleyways in Cleveland and hurdle over them. Then he watched his fellow East Technical High School graduate Jesse Owens win a gold medal in front of Adolf Hitler at the 1936 Olympics. When Owens returned to Cleveland, Dillard made sure he made it into the city for the parade in Owen’s honor. Dillard often recalled Owens winking at him, igniting his passion to win a gold medal, just like Owens.

Five years later, Dillard said that Owens gave him a pair of shoes. Dillard told the Cleveland Plain Dealer that he won the state championship in that very same pair of shoes.

When Dillard graduated from high school after winning states, Ohio State University attempted to recruit him as their next track star. Dillard’s teammate at Baldwin Wallace, Ted Theodore, said it helped their cause that Owens, another Olympic gold medalist from East Tech, had attended there. At first, it appeared Dillard might follow him.

“So, he goes and it’s three or four days and everything is fine except one thing: It’s not home,” Theodore said. “And Harrison missed home.”

Theodore, who also attended East Tech and graduated from Baldwin Wallace in 1951, said that after that visit, Dillard called Coach Eddie Finnigan at Baldwin Wallace asking if there was still a spot on the team for him. Finnigan told him there was.

Dillard began attending Baldwin Wallace College in 1941 but was drafted in 1943 into the Army during World War II. He ended up spending 32 months overseas as part of the 92nd Infantry Division.

After WWII ended, Dillard had the opportunity to participate in the “GI Olympics” hosted by the Army, where he impressed nearly everyone in attendance by winning four first place awards. One particular admirer stood out to Theodore.

“Then General Patton, who commanded the tanks, saw him at the meet and said Harrison was ‘the best goddamn athlete I’ve ever seen,’ and that was coming from the big cheese,” Theodore said.

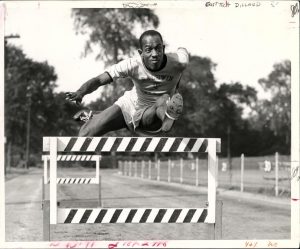

After returning to Berea, Dillard realized his Olympic aspirations were still alive. As a student athlete, he began winning and winning often. While on campus he won 82 consecutive hurdling races and four NCAA championships.

Theodore recalls it was clear from his earliest days on campus that Dillard was a special talent.

“Harrison and I would train at our track, and I wasn’t a sprinter but more a distance runner, but we would practice together,” Theodore said. “He would beat me, and then he’d give me a five-meter head start. And by the time I took my fifth step with the head start he would already pass me. Finally, we got to 10 meters [head start], and I was finally able to finish within a step of Harrison.”

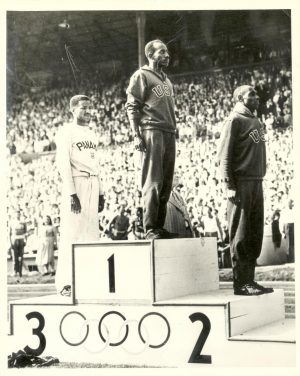

His true challenge came when Dillard traveled to London to compete in the 1948 Olympics. There, he won the first two of his four gold medals as he shockingly won the 100-meter dash and as part of the 4×100 relay team.

Still, he was known more for hurdling — the New York Times called Dillard the “world’s best hurdler in the 1940’s” — and his 82-consecutive hurdle victories held up as a record number until the 1980s. At one point he also held the world record times for three hurdles events: 60-yard, 110-yard, and 220-yard.

But Dillard still had not shown he was the world’s best hurdler at the Olympics. In 1948, Dillard failed to finish the hurdling final. After hitting numerous hurdles, Dillard fell behind and out of rhythm and failed to finish a race for the first time in his career.

“I never felt more guilty,” Theodore said. “We had improved his sprints so much that his timing for the hurdles was off. So, in the hurdles he should have ran at 90% and not 100% but he had the best start in the 100-meter dash and won the race by just a step.”

Four years later, Dillard proved he was world’s best at hurdling and won the gold medal at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics.

Even after his Olympic triumphs took him around the world, Dillard decided to make northeast Ohio his home. For years, Dillard worked as a sportscaster for WERE in Cleveland Heights and he also worked in the public relations department for the Cleveland Indians and held multiple roles on the Cleveland Board of Education. Dillard also assisted with the Marion Motley and Earl Browne Memorial Scholarship, with Ben Davis, a former Cleveland Browns cornerback and proponent of the scholarship. Davis was drafted by the Browns in 1967 after attending Defiance College. He said he always found Dillard to be an inspiration.

“I saw Harrison was going to a DIII school, bigger than Defiance, and I saw his accomplishments and said to myself, ‘I could try to do something like that,’” Davis said.

It was obvious to Davis, then, to jump at an opportunity to work with Dillard on the scholarship. His role was instrumental in the program’s success, Davis said.

“Harrison was always there to bring attention to what we were trying to do in terms of bringing in college scholarship money for kids from Cleveland,” Davis said. “He was very active in the community and helped quite a bit in terms of the attention and his presence.”

Other Cleveland Browns players from that era also remembered the impact Dillard had on them. NFL Hall of Famer Paul Warfield grew up in Warren, Ohio, playing multiple sports including track and field. Warfield remembers how large a role Owens and Dillard played as role models. Even at a young age, he knew he wanted to be like them and before Warfield decided to attend Ohio State for football and eventually pursue a career in the NFL, he was an Olympic prospect in hurdling, sprints and broad jump.

“I grew up looking at Harrison and Jesse and had always tried to come close to their records, but I could never surpass them,” Warfield said. “I admired Harrison as a phenomenal hurdler, who turned out to be the world’s best, and when I got to Cleveland [as a member of the Browns], I got to know him personally, and I was able to see his leadership in the community.”

For most in Northeast Ohio, Dillard’s legacy will always be the gold medals and his world records. But for Baldwin Wallace, his impact goes further.

With his passing earlier this week, the campus community is lessened, said Helmer.

“I would tell our students that if you didn’t have the chance to meet him, you missed meeting a hero,” Helmer said. “Many students had the chance to meet him, because he loved to interact with them, and they were the ones that were able to meet one of the giants of Baldwin Wallace.”

Those students who have not met him have likely walked past the statue in his likeness leaping over a hurdle outside Finnie Stadium, which was unveiled in April 2015. Theodore said presented the idea to honor his former teammate and led fundraising efforts.

“I was with some track officials and having lunch and they asked why Harrison didn’t have a statue, and it hit me,” Theodore said. “I’ve known the guy for 67 years, and I was his teammate. If I’m not going to do this, who would?”

Theodore went to a local sculptor and had a 14-inch replica made and brought it to Helmer.

“I said Bob, I think this is an important thing for us to consider,” Theodore said. “He turned to me and said he loved the idea and that now we needed to raise the money.”

Theodore was able to raise over $100,000 in just four months. Soon the 14-inch sculpture became a life-size statue.

“And at 91 years of age, Harrison was here for the unveiling and was the proudest man in the whole world at that time that they made something and it’s on the campus of Baldwin Wallace where he earned his stripes,” Theodore said.

The statue is not the only monument to Dillard’s legacy on campus, however. In the Lou Higgins Center on campus, you will find the Harrison Dillard Track, and a plaque highlighting his accomplishments hangs on the wall nearby. On the other side of the building, in the Hall of Fame, you can find a jersey that Dillard wore, as well as replicas of the four gold medals Dillard won.

Theodore, who worked with Dillard all those years before he reached Olympic glory, said he hopes current students will take inspiration in Dillard’s successes, but more importantly in how he earned them.

“If you came to practice early, Harrison was already there,” Theodore said, “and if you stayed late, Harrison was going to stay later. He was a champion because he was willing to work more than his competitors.”

The Exponent is looking for financial contributions to support our staff and our newsroom in producing high-quality, well-reported and accurate journalism. Thank you for taking the time to consider supporting our student journalists.